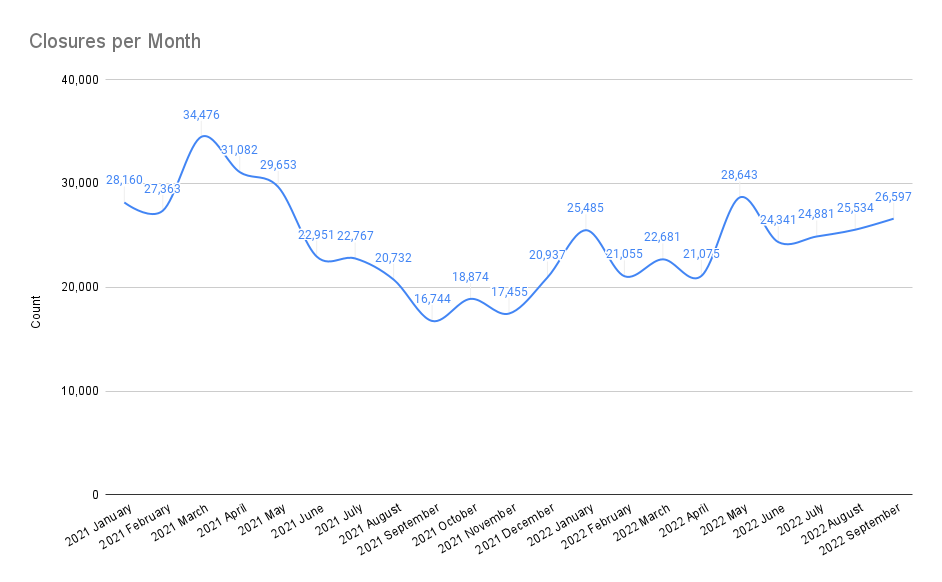

If you are an active online chess player, you might have noticed a troubling trend: more people are resorting to cheating. Each day around 3,000 accounts are closed on chess.com (based on 2023 numbers) due to fair play violations, which is triple as many as in 2021 and 2022.1

The issue of cheating in online chess isn't unique to chess but affects many competitive online games as well.

So why do some people feel compelled to cheat in online games?

Let's try to understand the psychological and contextual reasons behind this behavior instead of just shaming the cheaters. If we have a better understanding of the problem, we will be better able to combat it.

I have read the paper “Why Do Some Users Become Enticed to Cheating in Competitive Online Games? An Empirical Study of Cheating Focused on Competitive Motivation, Self-Esteem, and Aggression” (Front. Psychol., 29 November 2021) from which I will present the main reasons for cheating in online games. The paper reviews a wide range of papers on the subject.

The drive to win

According to the paper, one big reason players cheat is their intense drive to win. Chess is a game of skill, and for some, the pressure to succeed can be overwhelming. They want to gain prestige, win tournaments, or climb the rating ladder.

This competitive motivation can push individuals to use unfair methods, like chess engines, to secure victories. As one study pointed out, "Gamers with a high degree of competitive motivation are more inclined to cheat in the game".

Self-esteem issues

Self-esteem plays a crucial role in whether someone might cheat. Players with low self-esteem might cheat to avoid the sting of losing and to boost their self-image. On the flip side, those with high self-esteem are less likely to cheat because they find satisfaction in winning through their abilities and have experienced the payoff of success.

The research indicates, "Self-esteem decreased the degree of cheating but did not affect competitive motivation".

Aggressive tendencies

Aggression is another significant factor. Some players cheat as a way to channel their frustration, anger, or desire to dominate their opponents. Those with high levels of aggression might see cheating as a way to assert control and gain an unfair advantage.

The study found that "Aggression increased cheating behavior and had a significant relationship with competitive motivation".

The safety of anonymity

The online world offers a degree of anonymity that can make cheating feel less risky. When players believe they can cheat without being caught, the temptation grows. Even titled players can have their accounts restored on Chess.com as long as they admit to cheating without it becoming public.

This lack of accountability can erode ethical standards, making dishonest behavior more appealing. According to the paper cheating often involves "actions designed to obtain personal gains with the use of various dishonest methods, such as deception, fraud, and violation of rules".

Besides anonymity, it is also incredibly easy to create a new account on Chess.com and Lichess. The only thing you need is another e-mail address.

Peer influence

Peer behavior also plays a role. If players see others cheating and think it's common or accepted, they might be more likely to cheat themselves. This social learning effect can perpetuate cheating in the community. As noted in the study, "Cheating in competitive online games shows a tendency to spread to the community through victimization and observation" (Kim and Tsvetkova, 2020). The paper first states strong empirical support that cheating is contagious.

“The empirical support for the contagion of antisocial behavior is much more robust and consistent in the context of non-violent crime. Much of the evidence comes from tests of the “broken windows” hypothesis (Wilson & Kelling, 1982). The theory posits that minor infractions such as graffiti, litter, or vandalism can signal the absence of monitoring, enforcement, and public support of laws and social norms, encouraging such behavior, and leading to a self-reinforcing downward spiral. Field experiments have revealed that if people witness minor norm and law violations, they become more likely to litter, trespass, and steal (Cialdini et al., 1990; Keizer et al., 2008). In the lab, participants who observe other group members steal, cheat, or defect in cooperation games become more likely to do that too (Falk & Fischbacher, 2002; Gino et al., 2009; Jordan et al., 2013; Dimant, 2019). In schools, the presence and awareness of cheaters are associated with higher rates of academic cheating (McCabe et al., 2001; Carrell et al., 2008; Rettinger & Kramer, 2009). And in online forums, incidents of trolling and swearing cause others to exhibit verbal aggression (Cheng et al., 2017; Kwon & Gruzd, 2017).”*

*This might also mean that it is a bad idea to play vigilante with cheaters as Rozman does in the above video.

The paper explores how cheating spreads in online multiplayer games through observation and victimization. It hypothesizes that observing or being killed by cheaters increases the likelihood of starting to cheat, with the strongest influence from repeated exposure.

Data from over 1.1 million PUBG matches was analyzed, identifying cheaters based on bans for unauthorized tools. Networks tracked cheating adoption within 7 days after exposure. Results showed no significant increase in cheating from observation or victimization alone, but a combination of both significantly increased cheating likelihood, especially with repeated exposure.

The study concludes that cheating spreads primarily through combined observation and victimization, particularly with repeated exposure.

The current content creator climate around chess could therefore potentially fuel victimization, and thereby increase the likelihood of a player starting to cheat if the player experiences cheating as well.

Stress and gaming culture

The culture of online chess and other competitive games can add to the problem. High goals, intense pressure to win, and the fear of failure can push players toward cheating.

The gaming culture sometimes glorifies specific milestones, which can exacerbate the issue. The study highlights that "competitive online games strongly provoke users’ competitive motivation through situational cues (i.e., competition and reward)".

Cheating tools

A final explanation for why people cheat is that it is relatively easy and the tools are available online. I have looked into what people find if they decide to start searching for a tool for cheating on Google. The tools nextchessmove.com and chess-bot.com jump up.

Next Chess Move lets you set up a game position and lets you pick between a large range of engines to give you the next move. The site is running ads and sells a premium package. Chess-bot.com gives you the option to buy a program that will show moves directly on the screen, moves for you, and you can adjust playing strength, and a lot more.

Both sites have seen similar growth curves since the beginning of 2021. The growth of the cheating tool sites coincided with the online chess boom following the success of The Queen’s Gambit and the first viral cheating incident:

In March 2021, an Indonesian player identified as Dadang Subur played a computer-assisted game against Levy Rozman, obtaining over 90% accuracy. Rozman identified a pattern of cheating and reported Dadang's account. The Indonesian media claimed that Dadang was a legitimate player, inciting an online firestorm against Rozman. Dadang's subsequent match against IM Irene Sukandar received 1.25 million live viewers on YouTube, a historic record for a chess stream. Dadang lost three consecutive matches to Sukandar, with an accuracy of less than 40%.[60] Wikipedia

The online chess boom brought in a lot of new casual players unaware of chess etiquette and attitudes toward cheating. In turn, the content creators started to create a lot of content about cheating. This might have generated more traffic to the cheating sites.

If we look further at the traffic journey of users visiting chess-bot.com 7.18% travels to chesskid.com afterwards. The first mentioned study also listed that older players are less likely to cheat compared to younger players.

Finally, we can expect more tools to be developed since the developers have an incentive to either earn money on the search traffic or just break the system because they can. Below you can see an example from GitHub of what is mentioned as a program that is almost impossible to detect.

Final thoughts

“You see I kept asking myself then: why am I so stupid that if others are stupid—and I know they are— yet I won’t be wiser? Then I saw, Sonia, that if one waits for everyone to get wiser it will take too long….”

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

During dinner, I shared with my kids that I was writing a newsletter about cheating in games. I asked them if they had ever cheated in games, why they did it, and whether they thought it was acceptable. My oldest (11) told me he sometimes took money from the bank when we played Monopoly. I asked, why would you do that? To which he replied: “because otherwise the game is not fair and you will win.”

This conversation reminded me of Dostoyevsky’s classic Crime and Punishment, where the young Raskolnikov tries to justify his crime. He goes to great lengths in his mind to justify killing an old lady from whom he can steal money. Similarly, players might justify cheating to level the playing field or ensure their success. In the Say Chess chat, I asked before publishing, why someone would cheat:

“…in my experience, in school people who cheat normally don't think they are cheating. So I'm guessing it's something similar. Like people saying "oh, I won't look at the move, just the evaluation" or "I only look at 1 move per game" or "I want to see what the engine says but I'll decide myself if I want to do it." or some other rationalization that's actually ridiculous but which they think means that they are not really cheat.”

— stronghand14

To sum up, cheating in online games and chess is a complex issue. It can be driven by a range of factors: competitive motivation, self-esteem issues, aggression, anonymity, peer influence, age/maturity, and poor gaming culture. It seems like the influx of new players during the chess boom and the growth of online chess creators created a fertile environment for cheating.

It might be discouraging to read the above breakdown, but I think it is important to objectively look at the facts instead of the current online mud-throwing debate on twitter, which is leading nowhere.

Tackling the problem requires promoting ethical behavior, which doesn’t drive as many likes, clicks, or views on YouTube and other social networks. I have however tried to think of a few suggestions:

Better onboarding: Platforms could do more when onboarding new members. For example, making those under 18 watch a video about the negative effects of online cheating before letting them play with adults.

A pool for new accounts: Implementing a separate pool for new accounts could be beneficial. After 6 months, new accounts could gain access to the full player pool. This might create a worse experience for newer players initially but would make mature accounts more valuable, giving cheaters something to lose since they would have to start over on a new account if they get caught.

Take care of people who just faced a cheater: Since there is evidence that people who encounter cheaters are more likely to cheat themselves, it would make sense to pair players who have recently played against a caught cheater with accounts that have a high credibility score (accounts that have a high number of games and have been thoroughly checked). This would give the players a chance to cool down and reinforce their belief that there are still good, honest players in the world.

If you have good ideas of how the chess community and chess platforms can stop the cheating problem, please add a comment.

/Martin

Great analysis, Martin. I love the idea of a new player pool. I see many upsides. I think it would need to be a time x number of games threshold to help cut down bogus accounts. Licheas has something kinda like this with the provisional rating where players can't participate in certain tournaments with a provisional rating.

Thank you for bringing thoughtful analysis (and Dostoyevsky!) to the discussion.

Thanks for this, Martin.

I'm a low-rated player on Chess.com who only plays daily games (24 hours between moves). I play against other low-rated players. It's gotten so bad that I check each opponent's recent games to spot the cheaters, and abort games when I think I spot them. This is the behavior I've been taught because of all the cheating!

Then, about 30% of the time, a low rated player makes a series of perfect moves (brilliant ones, even), and I say to myself, "nice engine". And this makes me even sadder, because either my opponent started cheating, which stinks. Or worse, they're not cheating but playing focused, sharp chess. And rather than give them credit, my mind is automatically assuming they're cheating because of the ecosystem we're in.