The Botvinnik Method For Chess Improvement

If you are going to make your mark among masters, you have to work far harder and more intensively, or to put it more exactly, the work is far more complex than that needed to gain the title of Master

Welcome to this week’s newsletter of Say Chess. The newsletter now goes out to 3,383 subscribers. If you have not yet subscribed consider doing it if you like subjects like chess improvement, chess book publishing, and articles about the chess world.

New subscribers receive a free eBook with 14 annotated games by Capablanca.

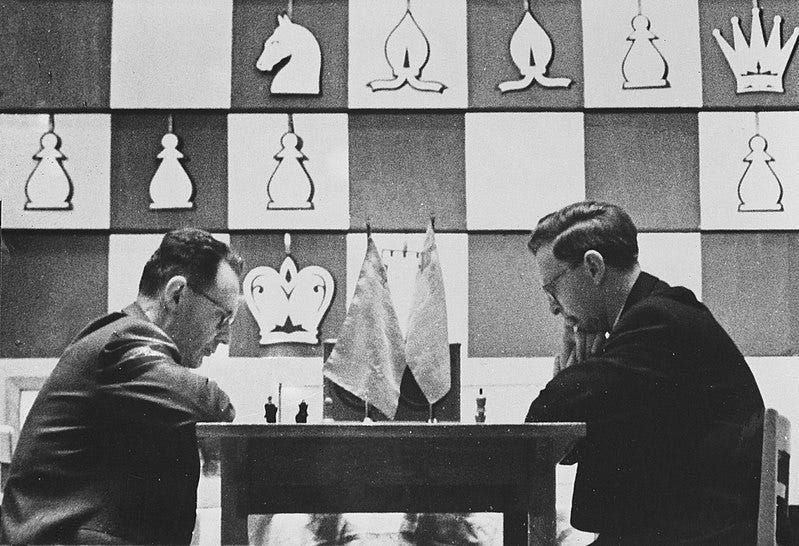

Some time ago I bought Botvinnik’s ‘One Hundred Selected Games’. I got it in a secondhand bookstore together with some other classics. I have only played through a couple of the games from the book, but the foreword is worth the price of the book in itself. It contains Botvinnik’s thoughts on chess improvement. Which I think is quite relevant still today.

Besides his very impressive competitive achievements, Botvinnik also made significant contributions to chess theory and practice, especially in the areas of opening preparation and the training of young players. He founded the Botvinnik School of Chess, which produced a number of world-class players such as world champions Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov, and Vladimir Kramnik.

So he must have gotten something right in his approach to the game. Let us take a look at his advices for chess improvement.

The Botvinnik Method For Chess Improvement

Let us start with the foreword of his book. He starts by describing what effort it takes to reach master strength.

”If you are going to make your mark among masters, you have to work far harder and more intensively, or to put it more exactly, the work is far more complex than that needed to gain the title of Master. To begin with, you find yourself up against experienced, technically well-trained tournament players. And then, if your advance is swift, others play against you far more energetically.

And, thirdly, every successive step up the ladder grows more difficult. At this stage you have to learn how to analyze and comment on games, for that enables you to criticize your own failures and successes. You have to accustom yourself to practical study at home, you have to devote time to studies, to the history of chess, the development of chess theory, of chess culture.

Finally, You have to acquire more experience and, in a few words, to grow a little older. All this took me about six years (1927-33)”

Botvinnik explains the importance of learning to analyze and annotate games. He published several books and wrote for publications, where he submitted his annotations and practiced this important skill.

“I had, too, to perfect my analytical powers.”

Training one’s analytical abilities is a core skill for Botvinnik, and he points out that the essence of chess is to master the ability to analyze chess positions. It sounds so simple, but in reality it is extremely difficult.

He writes that you should not call notes taken a few hours after the game for annotations, since this will, in Botvinnik’s opinion, have a negative influence on you. I interpret this as that you need to really dig deep and see annotations as a task that demands your full concentration and takes time and effort. Not just your thoughts during the game.

“..Chess is the art of analysis.”

His advice for avoiding sloppy annotations is to publish them. By doing this the annotations will be able to be criticized and that will help you stay sharp.

Botvinnik is as serious about tournament preparation as he is about annotations. He recommends that you go out to the countryside for 14 to 20 days before a tournament to detox and enjoy the fresh air. So, if your spouse asks, just say that you are following the Botvinnik approach. Here are some other key points:

Play training games and focus on the clock as the primary thing, not the quality of the games. By doing this you will learn to make the best use of your time ultimately teaching you to use the time optimal during tournament games.

Do not prepare shallow on all opening theory, but go deep on 3-4 openings for each color.

“If you are weak in the endgame, you must spend more time analysing studies; in your training games you must aim at transposing to endgames, which will help you to acquire the requisite experience.”

Review chess literature and take notes, and learn about new interesting games and ideas.

In my search for material about Botvinnik’s approach to chess improvement, I found an interesting interview with Kasparov from the KasparovChess podcast. Here is a transcribed quote:

”Botvinnik believed that the best way to help young players to advance was not just to analyze games with them and give professional advice but also to socialize. That's why our sessions lasted for seven to ten days and included many other activities like skiing, playing football, other sports and of course endless conversations where Botvinnik was eagerly sharing his chess career, telling us about great champions of the past like Capablanca, Alekhine, and by doing so, helped us understand the nature of the game of chess at the highest professional level.

During sessions, each of the students had to demonstrate four games and Botvinnik always insisted that the selection should include at least one lost game. Typically, it was two wins, one loss, one draw. And he always encouraged other students to make comments to be actively engaged during the analysis. Needless to say, it was a golden opportunity for me and I was probably too active and often Botvinnik had to slow me down saying that I was too fast and nobody could calculate lines so quickly and I should give others, or himself, time to think.

Sometimes he even said, "Garry, if you rush, if you make moves without proper consideration, you could become another Larsen or Taimanov." At first, I was not sure why that was a reproach and not a compliment because Taimanov and especially Larsen were among the best players in the world. But then I understood that for Botvinnik with his very solid positional approach and his almost religious belief in serious preparation, those were not players to be followed. Taimanov for his lack of seriousness and professionalism because Mark Taimanov was an excellent piano player and combined chess with music. And Bent Larsen for playing unorthodox chess, ignoring some traditional norms and ideas that for Botvinnik were cornerstones of good quality chess.”

Again it is hard not to notice the emphasis on analysis and sharing that analysis with your peers as central to Botvinnik’s training method. I find the Larsen and Taimanov horror comparison funny. Bent Larsen did interestingly enough not believe that there existed a specific Soviet chess school. In 2004 he wrote an article in the Danish chess magazine, ‘Skakbladet’, about chess schools. About the Soviet chess school, he wrote:

“The best attempt to define the Soviet chess school is based on a word that was fashionable during a couple of Danish election campaigns in the 1960s. Television had become crucial, and the goal was to appear on the screen and say 'concrete' many times.

In chess, 'concrete' seems to almost mean a reaction against Tarrasch. Perhaps even against Euwe. These two great authors, of course, understood more than their readers. The finer details often disappear in books and chess columns. But the Russians certainly weren't the only ones who discovered this.”1

When I read Larsen’s stance I get a feeling of arrogance, or “they should not believe they are so special”. When you read Botvinnik and about the Russian or Soviet Chess School we also have to remember the broader context of the cold war. Botvinnik was a man of the party and saw it as his responsibility to promote chess within the Soviet Union to glorify the state. By establishing specific traits of Soviet chess he helped in showing the superiority of the communist system. As he wrote in ‘One Hundred Selected Games’:

“We must go on developing chess throughout the length and breadth of our land, with the object of making many more workers both in town and country acquainted with the game. And our finest masters must play even better and create further artistic values.” 2

Now that the battle between capitalism and communism lies dead, the idea of the Botvinnik School lives on. The idea that deep analysis of chess is the way to reach chess mastery. A recent example is Gukesh who does not rely on engines as many other top grandmasters.

I’m sure Botvinnik would have been supportive of this approach as well since it seems to have forced Gukesh to work on his analytical abilities without relying on the engine, maybe more so than his peers. *Not that Botvinnik was against computers. He actually was awarded an honorary degree in mathematics at the University of Ferrara for his work on computer chess in 1991.

In general, the approach of Botvinnik to chess improvement demands iron determination and might be hard to follow for the hobbyist chess player. I must admit that I have tried and failed on this doctrine of annotating all my games. Not that it will deter me from trying again.

The recent success of the Chess Dojo training program demonstrates the enduring value of Botvinnik's approach. In my view, the Dojo program draws on Botvinnik's methods, particularly the emphasis on analyzing one's own games and sharing the analyses publicly. This underscores that following Botvinnik’s footsteps can indeed lead to noticeable improvement in one's chess performance - also for amateurs.

/Martin

https://skak.dk/images/skakbladet/2004/2004-01.pdf (translated from Danish)

Botvinnik, ‘One Hundred Selected Games’, page 29

Fantastic post Martin! I might need to steal that Kasparov quote for a chapter in my book 👀

Nice read, thank you! 🤩